of Equity members surveyed earn less than the median annual earnings in the UK

'Not here to help' - Equity members' experiences of UC and the Minimum Income Floor

A report for Equity by Heidi Ashton, Centre for Culture and Media Policy Studies, University of Warwick

of those on Universal Credit said it had not helped them to work in the industry

of those subject to the Minimum Income Floor had gone without food or utilities

Table of Contents

Preface: Paul W Fleming, General Secretary, Equity

Executive summary

Working in the cultural and creative industries

- The problem with current definitions of work

- The social security system: Universal Credit and the Minimum Income Floor

Research findings

- Pay, training and costs for Equity members

- Equity members’ experiences of UC

- The impact of the MIF

- What is the future for Equity members and the sector?

Conclusions

Recommendations

References

Appendices

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Appendix B: Full list of other occupations and sources of income

- Appendix C: Qualitative response regarding experiences of legacy benefits vs current system

- Appendix D: Case studies

Acknowledgements

Footnotes

Preface

Equity members have faced huge challenges over the last decade. Arts funding has been cut to the bone, first by Westminster, then by devolved and local governments acting under duress, and jobs have gone with it. A pandemic followed, throughout which 40% of our members did not receive a single penny of the government’s support package, despite its severe effects on creatives and the arts. Just as the worst health risks subsided, a cost-of-living crisis struck, deepening the economic damage done to our sector. The price of essentials has spiralled with only the bare minimum of additional government support.

This would be difficult enough for any worker to navigate and keep their head above water. But Equity members have been forced to do so without even the diminished safety net still available to those employed in other sectors.

The experiences that Equity members shared with us for this ground-breaking research were appalling. They spoke about financial hardship and debt, stress and anxiety, and the impossibility of navigating the very system of social security that we are all supposed to be able to rely on in times of need. Our union continues to fight the bosses at every stage to deliver decent work, sufficient rest and a living income for artists through our collective agreements. But these stories of hardship make it clear that we must press on a new front if we are to move from resilience to resistance – the strengthening of the safety net to properly support artists.

We all pay into the system when times are good, so that we can receive support when needed. This is a fundamental principle of any decent society, and one that we will not abandon. The recommendations of this report, based on the lived experience of our members, provide a strong platform from which to pursue this basic principle.

Equity cannot stand by whilst artists are treated as second-class citizens by the social security system. For all artists, and everyone in or out of work, we must fight to win a decent safety net.

Executive summary

This report uses new data from a survey of 674 Equity members, alongside six focused interviews, to analyse the experiences of social security of those working in the cultural and creative industries. On the basis of this analysis, it makes two recommendations for reform, to better support a workforce which directly generates £28.3bn in turnover and £13.5bn in Gross Value Added annually within the creative industries, which overall make up nearly 6% of the UK economy.[1]

The key findings are as follows:

Current employment status frameworks do not adequately respond to workers in the creative and cultural industries.

- Government frameworks for employment status vary between departments, with slightly different regulatory regimes across matters of employment law, tax and social security. This creates an overall framework that is challenging to navigate for all those workers without formal ‘employee’ status.

- This is particularly the case for those working in the cultural and creative industries, where the specific working conditions are not adequately recognised or addressed within these frameworks, especially under our social security system.

Universal Credit (UC) and the Minimum Income Floor (MIF) are not designed to respond to the conditions of work in the sector.

- Under UC, creative and cultural workers are tested to see whether they are ‘Gainfully Self-Employed’ (GSE).

- Once they pass this test, the UC MIF rule introduces an assumption that they are earning 35 hours at the National Minimum Wage (NMW). This reduces their UC payments by treating them as if they have earnings they do not have. In months where workers do earn more than this income floor, their actual earnings are taken into account.

- The design of this system does not recognise the short-term, project-based nature of work in the creative and cultural industries, where workers’ incomes can be highly variable. The MIF means that workers have their UC payments reduced or stopped in months where they are seeking work and need the support the most.

- Under the current social security system, Equity members are penalised by the MIF because of the precarious and insecure nature of work thrust upon them by the industry, instead of being supported to build a sustainable career in spite of this.

The government itself must recognise that the MIF has serious effects upon workers, as it suspended the MIF over the pandemic to support those struggling while the creative and cultural industries were unable to operate.

- Work in the creative and cultural industries is insecure, offering low take-home pay.

- Data from Equity’s survey demonstrates that:

- 95% of Equity members are considered self-employed by HMRC for tax purposes.

- 94% earn less than the median annual earnings in the UK.

- The average earnings of Equity members is £15,270 per annum from the industry, after expenses, but before tax.

- 63% of Equity members have been in receipt of social security at some point in their life, largely intermittently or for short periods.

- One in five could only survive for one month on their current savings. Over half have fewer than six months’ living expenses in savings.

The overwhelming majority of Equity members receiving UC have not been supported by it to find additional work in the industry.

- Four out of five members report that UC has not helped them to work in the industry.

- In contrast, three quarters of those with experience of our previous social security systems report that these had helped them to find work in the industry.

- Reflecting the way that production in the cultural and creative industries is organised, workers only claimed social security intermittently, and for relatively short periods. The majority of claims last between three months and two years, with intermittent claiming being the most common.

The MIF is driving these workers deeper into poverty and hardship, with very negative effects on wellbeing.

- By denying creative and cultural workers a full UC entitlement in periods without work but reducing their entitlement in months where they do earn, the MIF is driving serious financial hardship among workers.

- 41% of those subject to the MIF have gone without essential items such as food or utilities.

- 46% have been unable to pay bills for their household.

- 5% of respondents have been forced to leave their home as a result of the MIF. One told us that they were now living out of their car, following the MIF being applied.

- Nearly half of those who have been subject to the MIF are considering leaving the industry altogether.

- Case studies demonstrated the high levels of stress and anxiety being generated by the MIF rule.

Those implementing the system do not understand work in this sector, and struggle to navigate the complex rules of UC and the MIF. This creates additional barriers to accessing support.

- Respondents repeatedly reported the MIF being applied incorrectly or receiving incorrect information from work coaches.

- This has led to the MIF being applied unevenly between members with similar circumstances, depending on which work coach was responsible for implementing the rules, adding complexity, confusion and opacity to the system.

- There was a tendency for work coaches not to treat work in the creative and cultural industries as an established profession. This contrasts with the sector’s role as a major contributor to the UK economy.

- Little account is taken in the system for the high qualifications of these workers, or of the 12 hours a week they spend (on average) in additional training or the active pursuit of work (through auditions, for example).

This report makes the following recommendations for reform of our social security system, to better support workers in the creative and cultural industries.

Abolish the MIF. The test to decide if someone is GSE is sufficiently robust to ensure that bogus self-employment cannot be claimed. The MIF is superfluous and causes extreme and unnecessary hardship, anxiety and sickness. Other reports have also made this recommendation (Klair, 2022).

Initiate a full, evidence-based review of the effectiveness of the social security system in supporting atypical workers with multiple jobs and careers in non-standard work environments and sectors. These workers are important for contemporary industries as they provide a skilled, flexible workforce, but they do not fit into the current binary system. The review should test the current system for access to support, adequacy of provision, appropriateness and clarity of administration, and specific support needs. It should make further recommendations for reform following the abolition of the MIF.

Working in the creative and cultural industries

Equity members work across the cultural and creative industries. These sectors are dominated by project-based modes of production which rely on a flexible workforce, that is ready and trained to work on projects as and when they occur. This means that workers[2] are reliant upon numerous short-term contracts moving from one project to another. In order to do this, they juggle multiple projects simultaneously and engage in a range of work both within and outside the sector to sustain themselves between (and often during) professional projects and contracts.

These conditions of work and employment have led professionals working in this sector, despite high levels of skill, to be amongst the most precarious (Banks, 2017; Curtin & Sanson, 2016). This is because the labour markets and working practices operate largely outside of standard employment categories, norms and regulations. Without access to permanent or traditionally recognised forms of employment it is difficult for these workers to access financial credit such as mortgages (Ashton, 2021). The work is sporadic and precarious; workers generally find other types of employment to sustain themselves, although these jobs also need to be flexible to allow time to attend auditions and do the work necessary to gain more sector specific work. Performers can be informed of an audition the night before, leaving little time to prepare or notify other employers.[3]

A majority of Equity members also pay commission to their agents (with VAT). In this sector the worker pays for recruitment rather than the employer. These workers are also responsible for the costs of maintaining and developing skills rather than the employer. In this regard the workers take on many of the financial burdens and risks that would normally be the responsibility of an employer.

Workers in the cultural sector may also try to create work via grant applications. These take weeks to prepare - work that is unpaid. Access to funding is so complex that there is an industry built around providing grant writing services for those who can afford it. The success rate for funding applications is very low.

The precarious nature of employment within the sector means that it is more difficult for those from less advantaged backgrounds to develop or sustain a professional career. The cultural and creative industries have been criticised for the lack of diversity particularly in relation to class or more clearly socio-economic advantage (Brook et al. 2020). Those with access to support from parents or partners are able to sustain their careers through the ups and downs of life and work. Those without are increasingly left with no option but to leave the industry, thereby exacerbating the problems of diversity.

The problem with current definitions of work

Workers in policy and legal terms are defined under three options: ‘employee or employed’, ‘self-employed’ (including freelance), or ‘worker’. For tax purposes, a person is deemed either ‘employed’ or ‘self-employed’. For social security, a person is either a potential full-time employee or GSE, having passed a set of criteria[4] to determine the legitimacy of their ‘self-employed’ status.

These conventional notions and categories are misleading when applied to the employment situation that Equity members find themselves in. In the cultural and creative sector, professionals are usually considered self-employed for tax purposes and ‘worker’ for the purposes of employment law. However, their situation is complex, and the following sections outline existing definitions and contrasts these to the employment and working environment of Equity members.

The category of ‘employed’ or ‘employee’ suggests regular, standard, paid work, protected under employment rights and with PAYE tax status. These workers have access to paid annual leave, regular and predictable payments, sick pay, employer pension contributions, maternity leave, protection under the National Minimum Wage (NMW), working hours and health and safety regulations, protection from discrimination, and other related protections and rights.

The category of ‘self-employed’ is more complex but is generally associated with those who run their own business and have control over their time and resources. As such they do not usually have the same protections and employment rights as employees: “Employment law does not cover self-employed people in most cases because they are their own boss” (gov.uk, 2023). Government policy defines self-employment as someone for whom most of the following are true:

- They put in bids or give quotes to get work

- They are not under direct supervision when working

- They submit invoices for the work they have done

- They are responsible for their own National Insurance and Tax

- They do not get holiday or sick pay when they are not working

- The operate under a contract that uses terms like ‘self-employed,’ ‘consultant’ or ‘worker’

There are some exceptions in employment law. For example, those who are deemed ‘workers’ have access to some employment rights, which is an attempt to start bridging the gap between increasingly flexible labour markets and non-standard working practices (particularly in the gig economy). The complexity here is that some of these workers are deemed employed whilst other are self-employed in areas such as social security and tax where the status of workers’ reality does not exist in binary systems.

The final category or status often used in relation to Equity members is ‘freelance’. This is another poorly defined term that has no official definition in policy, employment or tax law. It can mean many things but is often associated with those who are free to choose which contracts to take, have some control over the fee paid, and can choose when and how they wish to work providing increased flexibility in their working lives. These workers are also ‘self-employed’ for tax purposes although also often work for an employer.

These categories fail to capture the unique complexity of employment situations that make up the working conditions for workers at the coal face of the cultural and creative sector. As such these categories are inadequate for the following reasons:

Employed

- There are few if any opportunities to be ‘employed’ in these professions.

- The project-based mode of production proliferates in the sector and workers are therefore reliant upon numerous short-term contracts that can last anything from half a day to 11 months.

- Skills levels are not linked to pay and there is no career progression.

Self-employed and freelance

- Fees for work are usually fixed by the employer and workers can be very poorly paid or unpaid.

- They do not generally have the option of putting in bids or quotes, and most fees are subject to deductions for agency fees.

- Workers do not always have access to full employee rights as they are either deemed ‘workers’ with some employee rights or ‘self-employed’ with none. Either way, they usually work under direction.

- Workers cannot generate work because employment is contingent upon the roles available and for the majority subject to the aesthetic conditions of the work (gender, race, height, weight, hair, etc.).

- Workers are reliant upon gatekeepers such as agents and social networks to access selection processes (auditions). They cannot bid for work in an open market.

- Selection processes are unregulated and can involve up to six auditions (recalls).

- Workers are required to attend auditions (or prepare self-tapes) at very short notice.

- Workers are not always advised if the final audition / meeting was unsuccessful.

- Workers are put ‘on hold’ or ‘on pencil’ for potential work dates which may or may not lead to paid work.

- Work can be cancelled at extremely short notice without any compensation.

Other complexities of working life

- Workers need to maintain links with agents and networks in addition to updating skills and marketing materials to continue gaining work.

- Workers often engage in a mix of fixed-term or zero hours PAYE contracts outside the sector whilst simultaneously juggling work opportunities in the sector.

- The availability of sector-based work is impacted by various external, political and economic factors over which they have no control and cannot mitigate against. The pandemic is an extreme example which completely stopped all production.

The social security system: Universal Credit and the Minimum Income Floor

Introduced in 2013, UC aimed to simplify the existing means-tested social security system and “bring together a range of working-age benefits into a single payment” (gov.uk, 2015). It replaces Housing Benefit, Income Support, Income-Based Jobseekers Allowance, Child Tax Credit, Working Tax Credit and Income-Related Employment and Support Allowance (‘Legacy Benefits’).[5] It was proposed as a means to increase incentives to work, reduce fraud and tackle “poverty, worklessness and welfare dependency.”[6]

Under UC, claimants are asked to self-identify as ‘employed’, ‘self-employed’, ‘both employed and self-employed’ or ‘unemployed’. If they answer self-employed to any extent, they undergo an assessment to decide if they are ‘Gainfully Self-Employed’ (GSE). The outcome of this assessment is binary: either GSE or not GSE. If they are deemed not GSE, they are provided with monthly payments to support rent and minimal living expenses, which are adjusted according to all income received and subject to a maximum level of savings. People with non-GSE status who do not earn enough are expected to look for any and all work opportunities and are sanctioned if they do not accept a job offer. This has led to criticisms of claimants being forced to take low-paid, low-skilled work regardless of their situation (DWP, 2023; Butler, 2016; Briken & Taylor, 2018).

Non-GSE claimants face additional problems if their work is offered on a self-employed basis. In modern labour markets, workers do not have control over whether their work is offered on a PAYE or self-employed basis. Those who have PAYE (including zero hours) contracts may be exempt from work search related requirements as part of their UC claim depending on their level of earnings.[7] This exemption only applies to those in PAYE, excluding those who are offered contracts on a self-employment basis. As a result, those deemed non-GSE can be penalised unfairly if their work is offered on a self-employed basis, which is the most common form of work available to Equity members.

Those deemed GSE are provided with UC, adjusted according to any income, but only for the first 12 months, known as the Start-Up Period (SUP). After this point, they become subject to the MIF. The MIF reverses the income support system, so that instead of income being ‘topped up’ to support minimum living standards (as it is with those who are not GSE), claimants are penalised through an expectation to earn a minimum amount per month. It is assumed that workers can earn the equivalent of 35hrs per week at their applicable NMW. If they earn less than this, it is assumed that this is because their business, as a self-employed person, is not viable. In plain terms, if your MIF is calculated to be £1,410 per month and you earn £800 that month, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) will calculate financial support based on the assumption that you should have earned £1,410,[8] and will only provide financial support above that amount. Effectively, those on lower incomes and deemed GSE receive nothing, whilst those deemed not GSE still receive support but must always be available for PAYE work.

For those working in the sector who, as outlined above, do not readily fit the definition of either ‘employed’ or ‘self-employed’ in policy and social security terms, the UC system (which assumes this binary definition of employment relations) is deeply problematic for the following reasons:

- They are reliant on work that is sporadic and unpredictable.

- They have no control over when the work is done or the fee they receive.

- A great deal of time is spent looking for and applying for work. This includes attending numerous auditions at short notice, compromising their ability to be ‘available for work’ at any time, as required by the employed status version of UC.

- They often engage in a mix of sector specific work and PAYE zero hours or fixed term contracts that are also sporadic and unpredictable in terms of both pay and time requirements.

The issues raised by Equity members sharing their experiences have also been highlighted in several other reports:

Creative Industries Policy Evidence Centre ‘Good Work Review’ (2023)

“There are ongoing concerns that those with fluctuating incomes or that experience interrupted periods of work are disadvantaged, both in terms of the threshold at which they are expected to look for or be available for work and in the use of the Minimum Income Floor in calculating Universal Credit payments. This was reported to frequently result in greater financial hardship for Creative freelancers …” (p.41)

The Institute for Policy Research ‘Couples Navigating Work, Care and Universal Credit’ (2022)

“Our research showed that significant ongoing ‘work’ is often required to maintain Universal Credit claims. These demands were especially burdensome in relation to childcare payments, but also related to shift work, zero-hour contracts and self-employment.” (p.16)

Trades Union Congress ‘A Replacement for Universal Credit’ (2022)

“The low-paid self-employed face an income penalty in Universal Credit, because of what is known as the Minimum Income Floor (MIF). The MIF only applies to the self-employed and assumes that self-employed people earn the equivalent of 35 hours a week at the national Minimum Wage when they access Universal Credit.” (p.6)

As more labour markets shift towards flexible working and workers engage in multiple careers, the creative and cultural sectors provide wider insights into contemporary work, and the effectiveness of social security systems in supporting workers in non-standard work and professions.

Research findings

Equity and the University of Warwick surveyed 674 of our members working in the cultural and creative industries, alongside six focused interviews with members with direct experience of the MIF. A full methodology is provided in Appendix A.

The following analysis builds on existing literature to examine the way that Equity members, as a highly skilled, flexible workforce, have used and experienced social security systems both now and in the past, with a particular focus upon the impact of the MIF. This is the first study to examine the efficacy of UC and the MIF in relation to these workers.

Pay, training and costs for Equity members

Key findings

Our data showed that:

- 95% of respondents are considered self-employed by HMRC for tax purposes.

- 80% of workers are professionally trained at a recognised institution.

- On average workers earn £15,270 per year from the industry after expenses, but before tax. 94% earn less than the median annual earnings in the UK.

- Workers spent an average of 12.1hrs per week on additional training (3.6hrs) and the pursuit of work including creating self-tapes, attending auditions, marketing and networking.

- Workers pay agents between 1% and 40% + VAT commission of any fees they receive for industry work, with 15% + VAT being the most common agency fee.

- There has been a decline in both the amount of work and the amount paid for work in the industry in the last year.

Training, costs and ‘working to get work’

Equity members work as actors, dancers, models, circus performers, presenters, entertainers, musicians, technicians, stage managers, producers and other performance and arts related roles. The work they do spans a range of sectors including those in the cultural and creative industries (predominantly theatre, film, television and marketing), corporate training, events, allied health and education in addition to work in the third sector, such as community arts.

Four in five respondents have received professional training at a recognised, institution. A majority (88%) attended this training full-time. The performing arts are often viewed as a hobby rather than a profession, but training in the UK for these professions is highly regarded globally. The Council for Dance, Drama and Musical Theatre have an accreditation system designed with industry leaders to provide “the industry benchmark of quality assurance for professional training.”[9] Sector training in the UK has a global standing and engagers will often seek out workers trained in the UK for jobs in global labour markets such as TV, film, theatre (including musical theatre) and cruise ships. Global producers such as Disney are attracted to film in the UK not only because of tax incentives but also the availability of a talented, well-trained workforce skilled in acting, singing and dancing, in addition to the leading expertise of CGI and related specialisms.

The standard occupation classification (SOC) for these workers is situated at skill level 3 which denotes ‘Higher level Occupations’ and covers higher level professional workers (ONS). All professional training requires an audition process, and for dancers, access to professional level training requires a significant amount of training with a professional provider, prior to auditioning. It is not uncommon for female dancers to commence dance training from as young as three years old and train intensively for around ten years in total (Ashton & Ashton, 2014).

To fund their training, a third of respondents had obtained local authority grants. This was the system prior to 1998 when people left school, often aged 16, and attended 3 years of training at a vocational college/conservatoire. 24% of respondents had student loans and 26% were independently funded for their 3-year training course, the remainder were funded through scholarships (14%) or a combination of funding sources.

While working professionally, respondents spend between one and ten hours per week continuing their professional training to maintain and update their skills. The average time spent was 3.6hrs per week. This is all self-funded.

In addition to this, respondents also spent significant time engaged with work-related activities that are not funded - ‘working to get work’. These activities include contacting agents, creating self-tapes, learning lines for auditions, travelling to and attending auditions, contacting networks, keeping social media updated, attending events and related workshops, or opportunities to network and researching the sector. The time spent on these activities varied, with more time spent when respondents were between jobs than when under contract. The time spent on these activities was between one and over twenty hours a week with the average being 8.6 hours. Combined with the time spent in training this is a total of 12.1 hours per week spent in either costly and/or unpaid work, to maintain professional standing and engage with future employment opportunities.

Work status, earnings and conditions of employment

95.4% of respondents are considered self-employed by HMRC for tax purposes, with the term ‘freelancer’ also used to describe this group. They have been working in the sector for between one and seventy-six years with the majority having between six and twenty-five years of experience.

Respondents lived in all four nations and across 144 main city areas, the largest group lived in London (38%) which is the geographical centre of the industry. There is no additional payment (London weighting) for those living and working in the capital.

64% of respondents were represented by an agent, there was no difference in earnings of those with or without an agent. Those working in stage management, technical roles and other backstage or behind camera roles will not be represented by an agent due to differences in labour market recruitment practices. Commission paid to agents was up to 40% (+ VAT) of gross earnings. The majority of workers are paying between 10% and 35% (+ VAT) depending on the job. Typically work in TV and film paid more and was liable for a higher rate of commission than theatre work. The increase in commission can leave the worker with the same actual income regardless of any increase in pay rate. 15% (+ VAT) was the most common flat rate paid.

Earnings from work in the industry averaged £15,270 per annum after expenses, but before tax. 60% earned less than £10,000 and 94% of respondents earned less than the median UK yearly earnings (ONS, 2023).

It is common for Equity members to work across a range of other sectors and occupations in order to subsidise training and work in the sector. This must fit around auditions, training, and the other sector-specific requirements necessary to continue being engaged in the sector they have trained for. Consequently, the majority of additional work is either zero hours PAYE contracts, part-time PAYE contracts, agency (temping) work, other freelance or self-employed work. Most undertake a mixture of these. The full range of additional occupations provided by respondents is listed in Appendix B with respondents commenting that they would do: “Anything I can get”, typically over multiple jobs - “I have multiple side-hustles; I work in events, front of house, crewing work, rigging, making props, making costumes, admin for arts companies. It’s exhausting.”

This work is completed in addition to the 12.1hrs per week spent pursuing work and training. Average earnings from external work are £13,100 per annum with a range of £0 to £70,000+. 72% of respondents earned less than £10,000 per annum from additional sources.

Just over half of respondents said they earned less this year compared to last year. This is broadly in line with other data on precarious environments, as recovery after the pandemic has been slow for workers in these sectors (IPSE, 2023; Blackburn et al, 2022). “It’s harder to get jobs. Wage remains the same and cost of life is higher.” Only 18% of respondents reported earning more than last year.

48% reported that they had spent less time working in the sector this year. The slight increase in those earning less compared to those working less suggests there has been both a drop in the amount of work and in pay. “I think the impact on the industry is felt more now in 2023 with all the ongoing cuts, there is less work available and it’s not a stable work environment as a freelancer.”

Respondents noted that a repeat job was paying less this year than in previous years or was no longer covering expenses. Workers were told that this is due to an increased cost of production and venue maintenance, resulting in squeezed budgets. Factors such as the cost of wood increasing since Brexit were reported as sources of production cost increases, leaving less budget for wages and travel expenses. This was reported across work in both the private and public sectors (Industria, 2023).

Although there are standard minimum pay rates agreed with Equity for some contracts, the commission paid to agents means that this is rarely the rate received by workers. In addition, workers pay for training (as described above), membership to recruitment sites such as Spotlight (from £172 per year), union membership fees, travel to auditions, equipment for self-tapes, professional photo shoots for profile pictures on Spotlight and for agents, and other work-related expenses. This represents a very significant individual financial investment in the pursuit of work.

Equity members’ experiences of UC

Key findings

- 82% of those on UC reported it had not helped them to find work in the industry.

- 75% of those on previous social security regimes reported it had helped them to find work in the industry.

- 63% of respondents had been in receipt of some element of social security in their life.

- The majority of claims lasted between three months and two years, with intermittent claiming being the most common.

- 15% of respondents have been subject to the MIF.

63% of survey respondents had been in receipt of some element of social security at some point in their career. 17% of those were specifically during the pandemic. These workers represent one of the groups that fell between the gaps of provision during the pandemic (OECD, 2020) due to the mixed nature of their employment status as PAYE and self-employed,[10] or because they were in the early stages of their career. One measure that did support members during this period was the suspension of the MIF, giving members access to UC.

For those who had been in receipt of social security prior to the pandemic, the majority claimed either Jobseeker’s Allowance, Working Tax Credit or Housing Benefit. The claims lasted between three months and ten years, with the majority of people claiming between three months and two years, usually on an intermittent basis. Three quarters of respondents who gained support prior to the introduction of UC said that it helped them to stay in the industry. Respondents said the benefits of this support were that: “I felt safe”, “It enabled me to engage in profit share work and similar that started me off”, “provided basics in uncertain times”, “helped me to pay for transport for auditions”, “helped me to survive”.

27% of respondents were currently in receipt of social security. The majority of these respondents were on UC, but as we are coming to the end of a period of transition between legacy benefits and UC, some were in receipt of child tax credit, working tax credit or other legacy benefits. 82% of those receiving UC stated that it had not helped them to gain employment in the sector, this is in contrast to the 75% who had received benefits in the past and reported that it had helped them.

95 respondents had been deemed GSE. The GSE test is designed to prevent fraudulent claims, by ensuring that the self-employment status is evidenced, not ‘bogus’. Those deemed to be GSE were usually provided with a one-year start-up period where the MIF was not applied. In this first year period, although claimants are not required to find permanent full time, PAYE work, they must record their efforts in seeking self-employment work. They must also demonstrate active steps to increase their earnings, for quarterly inspection by DWP work coaches. Failure to attend quarterly meetings can result in a sanction. If the work coach is not satisfied with the claimant’s efforts, they can end their start-up period. Those not considered gainfully self-employed are pressured to work full-time in cafés, supermarkets, and other low-paid jobs. Given their existing high-skill level, specialist training and qualifications, this was viewed by respondents as a form of de-skilling.

15% of respondents[11] had the MIF applied. Under this rule, instead of income being ‘topped up’ to support a minimum standard of living, as it is for other UC claimants, the self-employed are instead assumed to already be receiving a certain amount of income – usually set at 35hrs per week at their applicable NMW, even if in reality they earn less than this.

In 2023/24, the MIF at 35 hours for a worker over 25 years old is £1,410 per assessment period.[12] If they earn less than this, they only receive support as if they had earned the MIF amount, if they earn more, their support is also reduced to compensate for these additional earnings. It is applied regardless of income fluctuations. The MIF can stop or reduce payments for rent, children and childcare. This is even harsher than the worst sanctions imposed upon some out-of-work claimants under wider UC, who still receive housing element costs and other elements while being sanctioned.

The data above evidences that average yearly earnings for these workers is less than the minimum wage and they are therefore unlikely to meet the MIF threshold. Once the MIF is applied to the claimant’s UC award, the amount awarded is substantially reduced, and, depending on the calculation of the award, can result in no UC payments at all. “The amount of money I need to make to receive a payment is higher than the maximum amount of money I can make and still receive a payment. It’s ******g absurd. Why bother with the MIF at all? Why not just kick me off?”

The impact of the MIF

Key findings

- 41% of those subject to the MIF had gone without food or utilities.

- 5% of those subject to the MIF had to leave their homes.

- 8% of those subject to the MIF were considering leaving the industry.

- 5% of those subject to the MIF have already left the industry.

- The MIF created crippling anxiety both for those to whom it was applied and those who knew it would be.

- Respondents work beyond retirement age.

- Respondents were driven and motivated by passion and professional identity rather than money.

The MIF is applied to the entire UC award. However, sanctions applied under wider UC are applied only to the standard allowance for the individual or couple which protects UC payments for the household , for example for children and housing.

Though the severity of UC sanctions has been widely criticised, for those who are GSE the financial impact of the MIF is far greater than a sanction, leaving some with no support at all. For respondents, the effect of the MIF was: “Devastating! Had to turn to a food bank for 8 months as I had no income and no support from Universal Credit”.

The MIF leaves workers suddenly unable to afford their housing costs, bills, food or other necessities. Of those who were subject to it, 41% had gone without essentials such as food and utilities and 46% have been unable to pay bills. “It’s soul crushing. Sometimes I can’t afford to eat.”

Respondents looked for various ways to survive. “I pawn my jewellery to meet my basic needs”. Debt was often used to pay for basics such as rent and food. “I have had to use credit cards for essentials… I am in debt, it is stifling.”

For 5% of respondents, the MIF meant that they had to leave their home:

“I no longer have my own accommodation as this is not something I can afford. I live out of my car. And the offer of others to sleep on their couch or spare bed for a couple of nights… I rely on free car parks (which there are not many), and public bathrooms. Arts venues which offer free studio space are another space I rely on - finding somewhere to work from, keep warm, and charge equipment.”

Case studies 2 and 3 in Appendix D give further examples.

The impact of the MIF on health and wellbeing

The financial hardship and pressures of mounting bills, coupled with the looming sense that they will need to leave the industry after sustaining a career for many years, has had a devastating effect on both mental and physical health of respondents. The constant stress and anxiety of losing all income, their career and their homes, was overwhelming, and the impact devastating.

“I don’t eat, my heath has declined. I’ve even turned the gas off to my own home at stopcock as I can’t afford it. I sold my TV as I can’t afford a TV licence. I don’t live I exist... [following implementation of the MIF] Left depressed suicidal, worried about money. Physically health deteriorated”.

Respondents reported being diagnosed with anxiety and/or depression. For some it was so severe that they became inactive in the labour market due to the impact on their health. “I have been medically suspended from work, this adds major stress as I have struggled to pay bills and have been living off pot noodles to try and put my finances into housing costs”. Case study 2 in Appendix D provides a more in-depth example.

If this pattern continues, the MIF could leave people unable to work due to long-term sickness. This would have implications for the NHS and is counter to the objective of UC, which is to get people back in to work.

The impact on mental health was seen not only for those who had been subject to the MIF but also those who were waiting for the MIF to start. “I’m terrified. I will not be able to survive and will be in severe hardship.”

The impending MIF, coupled with a lack of understanding in relation to the labour market (detailed below), led to a loss of self-worth and confidence. “UC makes you feel worthless, even when you have a work coach who is understanding, the actual system makes you feel worthless. It sends me into constant severe anxiety attacks, and that my work isn’t worthy.”

This, alongside the financial hardship, was particularly problematic for those working in an industry that relies heavily on aesthetic and emotional labour. Workers need to look good, be confident in their performance and convey deep emotional states on command. The stress and anxiety of the impending MIF created further issues in delivering this. “There was a lot of stress about it though and fear, stress and desperation doesn’t mix well with performance or looking for work (no confidence - terrible).”

In general, whether respondents were deemed GSE or not, the UC system was seen as having a negative impact - “Universal Credit is the biggest stress in my life and I hate it.” The only comments that suggested UC had supported the respondent financially at a difficult time was during the pandemic. During this time the MIF was not applied. None of the respondents reported any positive effects of the MIF, the impact was universally negative.

It is also clear from this study that previous iterations of social security provision were able to provide support that enabled workers, especially those without other means of support, to sustain a career in the sector alongside supplementary income streams. By contrast, the MIF is forcing people into hardship and those without other economic resources are having to leave the industry and sometimes even their homes. Appendix C provides a table summarising qualitative data from the survey that compares respondents’ experiences of legacy benefits and UC. The case studies in Appendix D provide in-depth examples of how this combination of issues with the MIF impacts members’ lives.

Confusion in the system

Respondents were confused by the system and often reported conflicting information from the work coaches. Confusion tended to be around when and if the MIF should be applied. “So much time has been wasted being given incorrect information and thanks to Equity I received the year without MIF, but not without an unpleasant fight”.

The implementation of the MIF was variable and broadly dependent upon the personal interpretation of the people processing the claim (see case study 1 in Appendix D). Some Equity members sought support from specialists at Equity whilst others were told they were not eligible for any financial support as they had been self-employed for over a year already and assumed this could not be challenged. As a result of the confusion around if and when the MIF should be applied, the implementation of the MIF was not uniform across members. This supports other reports with similar findings in relation to the implementation of sanctions for UC more generally (NAO, 2016).

UC was initiated with the intention of simplifying the system and bringing a disparate group of benefits together. However, this simplification has led to a rigidity that conflicts with the very fluid nature of work and earnings that this group of workers face:

“Although my UC person was sympathetic she can only apply the rules. And it is helpless when you can earn one/two months and then the next you’re searching. Also, expenses. I was squeezed and squeezed to reduce my expenses – normally allowed by HMRC, but not by UC, so that they could give me less, effectively. Just cos they don’t allow things doesn’t eliminate my expenses.”

Creative and cultural work is treated as a hobby

The extent to which work coaches were sympathetic to the situation facing Equity members varied greatly, from being sympathetic but unable to assist to suggesting that their career was simply a hobby, despite the training and significant time, emotional and financial investment by the performer.

“The person there is a constant negative drain on me, pushing at me at every appointment for me to give up my work, telling me that I should find a full time, ‘normal’ job. I said I love my work. It not only pays over double what I would be paid doing an unskilled ‘normal’ job, but it is also highly fulfilling and meaningful. She told me everyone does work they do not like, that she hates her job and that I should ‘suck it up’” (see also case study 2).

Some respondents found it impossible to navigate the system and took alternative work until they could find more industry specific opportunities or left the industry entirely. “Unlike on the continent, where you can get government financial support if you work a certain number of days a year, our job is treated as a hobby, so I just gave up and took office work for a while.” This is one of the consequences of UC more broadly that has been criticised by employers who have noted that the current system creates a high volume of inappropriate applications for jobs that are not matched to the applicants’ “skills, capabilities and wider circumstances” leading to high turnover costs. Employers would prefer a system that enabled them to recruit “people who both want and are able to do their jobs” (p.3) (Jones & Carson, 2023).

Variable income streams and payment

The labour market that these workers navigate in their professional careers is extremely complex, unregulated and unpredictable, often termed non-standard work. There is no career progression as such, work is sporadic and can pay well over extremely short-term contracts (sometimes a few hours or a day) but there are many expenses such as agent fees and costs of training outlined above, in addition to preparation time that is also regularly unpaid. Other aspects of the industry that do not fit into a rigid social security system include the delay in payments. This is an issue for many freelancers across a range of sectors (IPSE, 2022) and was an issue highlighted by members in this study:

“The roller coaster nature of our income streams means that some months I have two thousand pounds come in, while this Jan I had £184. UC just can’t keep up with our reality”.

This reality is also an issue for budgeting: “I live day to day, late/delayed and non-payments from productions mean I am generally out of pocket for the work I do.”

Poor understanding of work in the sector

A more pressing issue for members when applying for social security was the lack of knowledge and understanding of performing work in this sector among work coaches. Both recruitment and employment in this industry are very different from standard labour markets, and this made it difficult for members to navigate the social security system or explain to work coaches what they needed to do in order to work in the sector. “UC does not work for actors it leaves them in an awful position, we have to spend all our time finding work outside the industry instead of looking for and preparing for work in the industry.”

Respondents reported frustration in trying to explain the unpredictable nature of the work and their need to find flexible employment to sustain themselves between industry related contracts, rather than engage with any job regardless of whether it would prevent them from engaging in their profession.

“At times, I have found myself sat across from someone who has immediately, and most openly, disengaged themselves from the conversation we were having just as soon as talk of the industry was mentioned.”

This left respondents with the impression that “UC didn’t recognise acting as work.”

The disconnect between this work and standard labour markets was keenly felt. Members were unable to apply their lived experience of work into the social security support regulatory framework. The current system does not recognise non-standard employment, and this is the only employment available in this sector.

The age of the workers in this report was between 21 and 94 with an average of 48, with respondents continuing working or intended to continue working well after retirement (see case study 4). They have been working in the industry between one and 76 years with the average being 29 years.

Given the low financial compensation they receive, money is not the motivation behind working in the industry. Qualitative data in this research and other studies (e.g., Banks, 2017) demonstrates that work in this sector is driven by passion and is deeply connected to identity. This lends further credence to arguments that punitive measures are not necessary in incentivising work-seeking behaviour among this group. For those who have had the MIF applied 5% have already left the industry and a further 42.8% are considering leaving.

What is the future for Equity members and the sector?

Workers in the cultural and creative industries are facing a challenging future: low pay, precarious work, a cost-of-living crisis, and the difficulties in juggling multiple jobs in order to sustain a career in the sector. This is exacerbated by a seeming lack of government support, be it gaps in the pandemic support schemes, UC provision, or ineligibility for cost-of-living payments.[13]

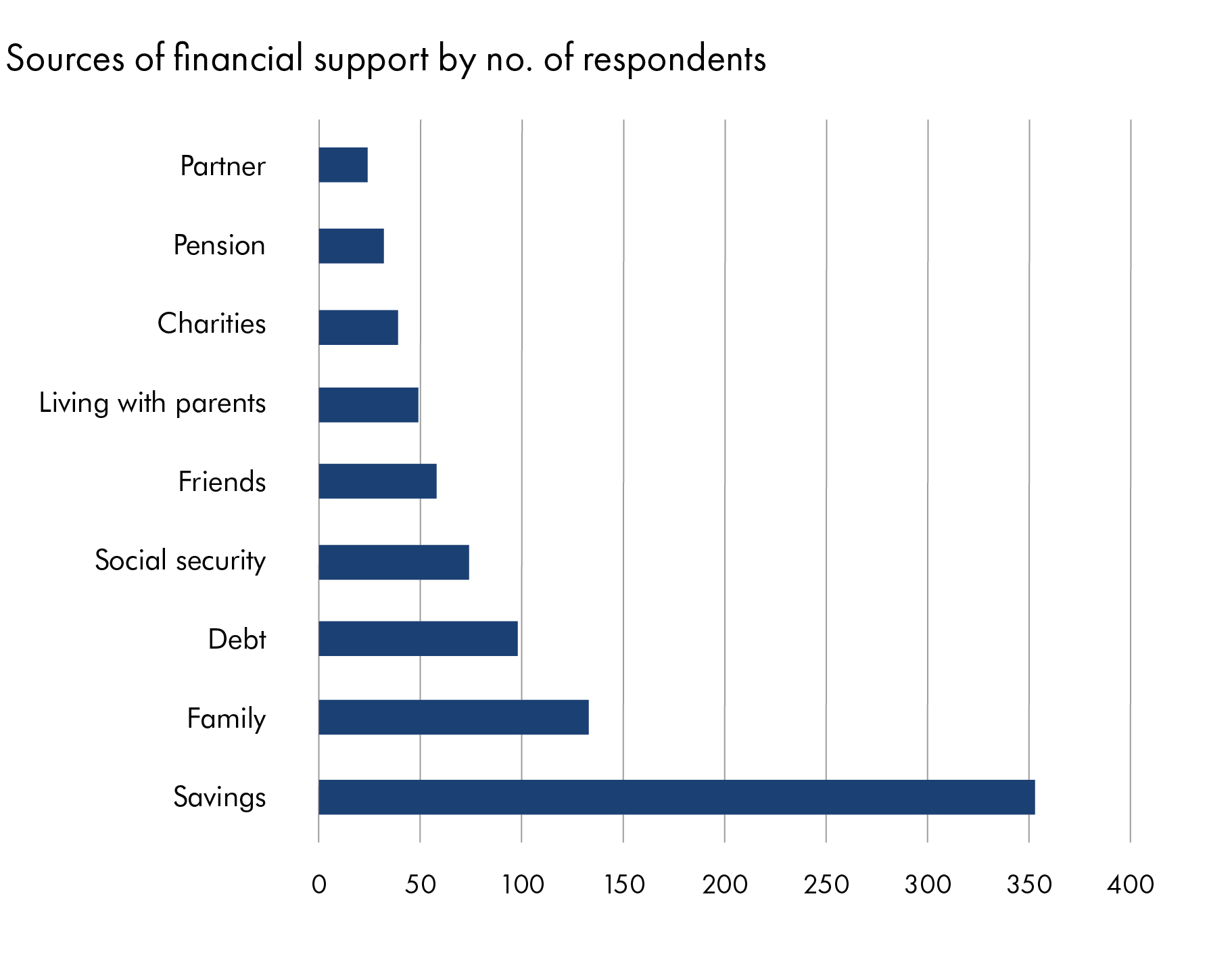

This proximity to crisis was apparent in the survey results. Most respondents are currently reliant upon resources outside of their main incomes. Over half are partly or wholly living on savings (see chart).

As the above chart shows, respondents were relying on various sources of support to sustain themselves and their families. Beyond this they were also reliant upon free school meals, buying discounted food, equity release, local libraries and emotional support from family and friends.

Some also benefited from the fees that are paid to workers in the sector if their work is shown after an agreed period of time or if a TV show or film is sold to be played on TV, on an aeroplane, or as a small percentage of DVD sales. In recent years there has been an erosion of this vital income derived from performers’ intellectual property (IP) rights, as producers increasingly favour the buy-out, in which workers sign away all IP rights for their screen work from the outset. This additional income is therefore likely to decrease significantly for a majority of workers.

Whilst many were reliant upon savings, 3.3% had no savings, 18.8% had enough money to survive for one month, 14.6% could survive for two months, 18.6% could survive for three to six months. In total, 73.4% would manage for less than a year. 8% of respondents have used a food bank in the last five years. All workers in this sector will keep some money from a lucrative contract aside as this is used to pay taxes, rent and living costs. In this respect, ‘savings’ are not necessarily indicative of disposable income but a fundamental aspect of this type of precarious work. Workers will go without clothes or other items in order to protect ‘savings’ that are for next month’s rent. Given the current concerns that the self-employed are 65% less likely to have started saving for a pension (DWP, 2022) more research is needed to find out the extent to which the savings that respondents refer to include pension savings.

Caring responsibilities also had an impact on respondents in terms of both working in the sector and navigating the social security system. A third of respondents provided care. 61% of this was childcare (as primary carers or grandparents), the remainder included caring for parents and partners. 72% of those providing care stated that caring responsibilities had impacted upon their ability to work in the industry. Respondents reported that juggling work in and out of the sector alongside the administrative burden of UC and caring responsibilities was overwhelming, this finding supports that of Griffiths et al (2022). The impact of the UC credit system and the MIF was most severe for the most vulnerable.

The sector has been heavily criticised for the lack of diversity and decreasing opportunities for those from lower socio-economic groups to work in the sector (Brook et al., 2020). This is supported by the data here which suggests workers need savings or other economic means to supplement their work in the sector, due to issues of low pay and intermittent work. This is a group of people who are willing and able to live frugally, motivated not by money but by passion for and love of their work. The MIF however is creating a barrier to their participation in the sector, forcing them to either leave the sector to work in full-time employment or be left without basic provision for housing or food. This is contributing to the talent drain in the sector noted in previous studies (Arts Professional, 2022).

Established actors such as Julie Walters and Julie Hesmondhalgh have spoken publicly about the decreasing opportunities for those without financial backing to gain entry in the sector. Julie Hesmondhalgh received support firstly via a local authority grant for training and subsequently via social security to support her in the early stages of her career and during times of hardship. She describes herself as ‘state sponsored’. Support provided to those from less affluent backgrounds has, in the past, enabled people to go on working and representing the UK in creative works that have been exported globally.

The current social security system does not serve people working in industries with non-standard work practices and employment relations. This leaves those who have trained in the sector with no support to build up a range of work that enables them to continue to pursue a career, unless they have independent financial support from elsewhere:

“One day soon I’m going to have to step into any old job that does not have capacity for me to take on work in the industry. I wonder then what all the years, time, sacrifice and expense of training and maintaining skill etc is for. I’ve sacrificed a lot to be able to do this work and yet I feel (in terms of Universal Credit Minimum Income Floor) like I’m regarded as a waster and drain to society. My profession and expertise does not feel regarded or respected at all.”

Currently the only option for Equity members facing the MIF is to move onto UC without being self-employed, and be subject to a requirement to take any full-time employment opportunities. This is detrimental to workers and increases inequality in the sector.

There is no evidence to suggest that there are economic savings to be made through the implementation of the MIF. Aside from the potential for people to become economically inactive due to the MIF, contributing to numbers that are already problematic (Boileau & Cribb, 2022), recent studies suggest that those on UC but not GSE are also unlikely to be in full-time employment after a year claiming social security. Johnson et al (2021) show that after a year on UC only 25% of claimants ended up in full-time employment.[14]

Furthermore, the IFS Deaton Review shows increases in the number of workers who are reliant on social security. In the 1960s, only the bottom income decile relied on social security for a fifth of all income. By 2019, this was the case for all incomes up to and including the fourth income decile (Bourquin et al, 2022). Moving working class people from a ‘gainfully self-employed’ status into underemployment[15] does not fulfil the purpose of the social security system, or the stated aims of UC.

Conclusions

The aim of UC was to increase incentives to work and reduce fraud, welfare dependency, and poverty. To take each of these in turn:

Has UC increased incentives to work?

The results here show that for this group of workers UC has not increased incentives to work in the sector or elsewhere. The impact of the MIF has caused some to withdraw from the labour market entirely due to illness. The choice between permanent full-time employment, which by definition means leaving the industry, or being faced with no support has not motivated or incentivised workers. Instead, it is forcing those without additional support out of the industry.

The study shows that these workers spend on average 12.1 hours per week actively looking for work and maintaining / developing skills, they are intrinsically motivated so punitive incentives are not conducive to positive outcomes. Working full-time outside the sector in jobs below their skill level, forcing them to leave their profession, does not do justice to the significant investment in training and is neither beneficial to the worker or employers.

There is no evidence to suggest that this group of workers are engaged in fraudulent claims

Those subjected to the MIF have:

- passed the GSE test

- are self-employed for tax purposes

- are professionally trained

- are in SOC level 3 identified as ‘higher professional occupations’

The data here shows that the definition of ‘self-employed’ under UC is too narrow and only acknowledges those running their own business with relative autonomy over when and where they work and how much they are paid. Workers in non-standard labour markets fall in between the gaps of a binary social security system, that views employment in terms of either permanent, full-time employment with a single employer, or self-employment in which the individual is reliant upon themselves and does not work for an employer. The reality is that contemporary labour markets are far more complex. There is a spectrum from standard, permanent, full-time employment to fully autonomous self-employment. This requires a rethink of social security systems to support the ‘new world of work’ (Schoukens & Barrio, 2017).

The labour market in this part of the cultural and creative sector does not offer permanent employment. Workers provide a flexible workforce and take on the majority of risk, in terms of investment in their skills and time taken to pursue work, whilst still being reliant upon producers to employ them. They do not have the same autonomy as a business owner, particularly when work is dependent upon both skill level and aesthetic considerations. However, they are self-employed for tax purposes and take most of the risks in terms of human capital investment.

This sector employs a project-based mode of production which is reliant upon a highly skilled, flexible workforce. This type of employment relationship is not recognised by the current social security system. This means these workers are not properly supported in pursuing their professional work. The previous social security system provided greater flexibility and, whilst not perfect, was more sophisticated than the current system in responding to non-standard working conditions.

It is argued here that DWP checks on self-employment as a legitimate status, and the monthly reporting system, weed out illegitimate self-employment and reduces the potential for over and under reporting income. The MIF therefore is not required to prevent fraudulent claims.

There is no evidence that this group of workers are welfare dependent

The IFS Deaton Review on inequality states that:

“In 1968 income from state benefits and tax credits made up a fifth of all income of the bottom income decile (and less for other income deciles); in 1978, this was true for the second decile too; by 1991, this was true in the third decile, and in 2008 and 2019, this was also true for the third and fourth deciles.” (p.2)

Those relying on welfare for a fifth of all income increased from the bottom 10% income group in the late 1960s to the bottom 40% in 2019. In effect, social security has been subsidising low wages to increasing degrees over the last 50 years. Whilst the respondents to Equity’s survey earned below the National Minimum Wage on average, they had usually spent only between three months and two years claiming social security, with intermittent claiming being the most common. This suggests that this group of workers are not ‘welfare dependent’, even though, under the Deaton report analysis, their wages suggest that they would be. Instead, these workers are proactive in finding work that fits around the labour market demands of the sector.

This study has found exceptional resilience and stoicism amongst this group, who are willing and able to work for very little as long as they can pay their basic bills, and only seek support when they are in dire need due to circumstances outside of their control. It is notable that when the country was faced with circumstances outside anyone’s control (the pandemic), the MIF was suspended.

Has UC reduced poverty?

Evidence from this report clearly demonstrates that the MIF in particular has significantly increased poverty. The implementation of the MIF has forced respondents to seek charity and support from networks, and sometimes to lose their homes. This has had a disastrous impact upon the wellbeing of many workers in the industry, some of whom have contemplated suicide. It has prevented people from being fit to work in the sector, as they are unable to perform under intense fear of losing their homes and professional identity, particularly those who have worked in the industry for a number of years.

As such, the UC system does not fulfil its aims and objectives for this particular group of workers and is damaging when the MIF is applied.

Recommendations

This study provides proposed policy options for next steps in remedying the flaws in UC:

Abolish the MIF. The test to decide if someone is ‘gainfully self-employed’ is sufficiently robust to ensure that bogus self-employment cannot be claimed. The MIF is superfluous and causes extreme and unnecessary hardship, anxiety and sickness. Other reports have also made this recommendation (Klair, 2022).

Initiate a full, evidence-based review of the effectiveness of the social security system in supporting atypical workers with multiple jobs and careers in non-standard work environments and sectors. These workers are important for contemporary industries as they provide a skilled, flexible workforce but they do not fit into the current binary system. The review should test the current system for access to support, adequacy of provision, appropriateness and clarity of administration, and specific support needs. It should make further recommendations for reform following the abolition of the MIF.

References

Arts Professional (2022) Arts Pay Survey. Available from https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/sites/artsprofessional.co.uk/files/administrator/arts_pay_report_22_final_0.pdf

Ashton, H. (2021) Comparative analysis of pay and conditions: London’s West End and New York’s Broadway, Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre and University of Warwick. Available from https://pec.ac.uk/discussion-papers/comparative-analysis-of-pay-and-conditions-londons-west-end-and-new-yorks-broadway

Ashton, H. & Ashton, D. (2014) Bring on the dancers: reconceptualising the transition from school to work, Journal of Education and Work, 29(7): 747-766 DOI: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13639080.2015.1051520

Banks, M. (2017) Creative Justice, Rowman and Littlefield: London

Blackburn, R., Machin, S. & Ventura, M. (2022) Covid-19 and the self-employed – A two year update, Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

Briken, K. & Taylor, P. (2018) Fulfilling the ‘British way’: beyond constrained choice – Amazon workers’ lived experiences of workfare, Industrial Relations Journal, 49(5-6): 399-552

Boileau, B. & Cribb, J. (2022) Is worsening health leading more older workers quitting work, driving up rates of economic inactivity? Institute of Fiscal Studies, Available from https://ifs.org.uk/articles/worsening-health-leading-more-older-workers-quitting-work-driving-rates-economic

Bourquin, P., Brewer, M. & Wernham, T. (2022) Trends in income and wealth inequalities, Institute for Fiscal Studies Deaton Review.

Brook, O., O’Brien, D. & Taylor, M. (2020) Culture is Bad for You, Manchester University Press: Manchester

Butler, P. (2016) Benefits sanctions: a policy based on zeal, not evidence, The Guardian, Available from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/nov/30/benefits-sanctions-a-policy-based-on-zeal-not-evidence

Curtin, M. & Sanson, K. (2016) Precarious Creativity: Global media, local labor (Eds); University of California Press: Santa Barbara

DWP (Department for Work and Pensions) (2023) The impact of Benefit Sanctions on Employment Outcomes: Draft report, Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-impact-of-benefit-sanctions-on-employment-outcomes-draft-report

DWP (2022) Planning and preparing for later life: research and analysis, Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/planning-and-preparing-for-later-life/planning-and-preparing-for-later-life

gov.uk (2015) Policy Paper: 2010 to 2015 government policy: welfare reform, Updated May 2015. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-welfare-reform/2010-to-2015-government-policy-welfare-reform

gov.uk (2023) Employment status. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/employment-status/selfemployed-contractor

Industria, (2023) Structurally F-cked: An inquiry into artists’ pay and conditions in the public sector in response to the Artist Leaks data, Industria, Available from https://static.a-n.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Structurally-F–cked.pdf

IPSE (2022) Late payment and nonpayment: Reviewing the prevalence and impact within the self-employed sector, IPSE Available from https://www.ipse.co.uk/policy/research/financial-wellbeing/late-payment-within-the-self-employed-sector.html

IPSE (2023) The Self-Employed Landscape Report, IPSE. Available from https://www.ipse.co.uk/policy/research/the-self-employed-landscape/self-employed-landscape-report-2022.html

Johnson, M., Martinez Lucio, M., Grimshaw, D. & White, L. (2021) Swimming against the tide? Street-level bureaucrats and the limits to inclusive active labour market programmes in the UK, Human Relations, 76(5): 1-26

Jones, K. & Carson, C. (2023) Universal Credit and Employers: Exploring the demand side of UK active labour market policy, Manchester Metropolitan University, ESRC report, Available from https://www.mmu.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-01/UniversalCreditandEmployersFinalReportJan2023.pdf

Klair, A. (2022) A Replacement for Universal Credit, Trades Union Congress. Available from https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/replacement-universal-credit

NAO National Audit Office (2016) Benefit Sanctions. Available from https://www.nao.org.uk/insights/benefit-sanctions/

OECD (2020) Culture Shock: Covid-19 and the cultural and creative sectors. Available from https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/culture-shock-covid-19-and-the-cultural-and-creative-sectors-08da9e0e/

ONS Standard occupation classifications

ONS (2023) Labour market overview, UK: May 2023: Estimates of employment, unemployment, economic inactivity and other employment-related statistics for the UK. Available from https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/latest

Schoukens, P. & Barrio, A. (2017) The changing concept of work: When does typical work become atypical?, International Labour Law Journal, 8(4): 306-332

Appendices

This project used a mixed methods approach, combining survey data with in-depth interviews. The rationale was to gain both an overview of members’ experiences and a nuanced understanding of the impact of the MIF on day-to-day lives. The survey provided a broad sample of members’ experiences in accessing social security systems in the past and the present. Deeper insights from members who had been impacted by the implementation of the MIF were gained via interviews, which make up case studies 1-4 provided at the end of the report.

Survey

All Equity members were sent an online survey via email. This resulted in 674 responses to 57 questions, providing data on:

- demographics

- work inside and outside the sector

- training

- pay

- caring responsibilities

- access to support

- experiences of social security

- experiences of the MIF

As this is a cross-sectional method, we also sought to include questions which illustrated changes over time in relation to work, pay and social security.

Sample

The study was designed to examine the experience of a group of workers in the cultural and creative sector in order to understand the impact of the MIF on them. It does not aim to look at intersectional vulnerabilities. Demographic data was gathered to check for potential subject bias (given the specific focus of the survey) and also to provide an overview of who respondents are. Caution should be exercised in relation to examining demographic data such as gender identification and ethnic diversity as different surveys use different categories.

The demographic of respondents was broadly typical of both the wider Equity membership and the UK population in terms of gender identification split, with the exception that there was a higher percentage of non-binary and transgender identifying respondents compared to the UK population as a whole:

|

Gender Identification |

Respondents |

UK Population (ONS) |

|

Female |

53% |

50.4% |

|

Male |

43.7% |

49.34% |

|

Non-binary / Non-conforming |

2.7% |

0.06% |

|

Transgender (male and female) |

0.6% |

0.2%* |

*This is broadly based on ONS statistical data but is difficult to determine as gender identity is often conflated with sexual orientation or whether someone identifies with the same gender assigned at birth and not provided within wider categories of gender identity such as male and female which this survey did.

The slightly higher percentage of female respondents (and Equity members) is potentially due to the inclusion of professional dancers which is a female-gendered occupation and labour market.

The percentage of respondents identifying as BAME was broadly similar to the UK as a whole with 17.8% identifying as BAME (UK 16.8%) and 82.2% identifying with white racial categories (UK 83.2%). There were significant differences in the split within BAME respondents with 9.13% identifying as mixed heritage as opposed to the UK population of 3% and there were further differences in terms of ethnic diversity within the BAME group, but it was not possible to examine this in detail due to differing group definitions.

Geographically all four nations of the UK and 114 broad city areas (postcode groups) were represented. The largest group of 38% lived in London boroughs. Brighton and Manchester are the next highest at 3% each, followed by Birmingham, Liverpool and Glasgow at 2% each. The significantly high percentage of those living in London is expected, as this has traditionally been the centre of the cultural and creative sector.

Respondents were aged between 21 and 94 with 12.4% of respondents aged 20-30, around 20% across the brackets 30-40, 40-50 and 50-60, 15.7% aged 60-70, 7.3% aged 70-80 and 1.1% 80-90+.

Analysis

Data for all questions was analysed to gain descriptive statistics. As a new piece of work with a focus on experience and impact of the MIF, correlations were not used in this study. Open-ended questions were also used to gain qualitative insights into the experiences of Equity members. This data was combined with qualitative data from the interviews into a thematic analysis, identifying key themes that were common across the membership and detailing the main issues that members faced in relation to social security and the MIF in particular.

Interviews

The interview sample consisted of Equity members who have been in contact with Equity seeking support in relation to their experiences with the MIF. Of those who agreed to be interviewed, 11 were contacted with the final six interviewees being those who responded to requests to meet and completed the informed consent documentation.

There was an equal split between male and female identifying participants; geographically two interviewees were based in London, two in Wales, one in Manchester and one on the South Coast. Interviews were conducted using a conversational style, including some initial biographical discussion for context, four in-person and two online. The four case studies provided in this report are taken from this group.

Unanticipated, additional data emerged from members emailing their experiences directly to the researcher. This data was added to the interview data for analysis.

Interviews were transcribed and thematic analysis used alongside the qualitative data gained from the survey and emails. This provided a more detailed understanding of the similarities and differences within the themes that emerged. The four case studies provided the clearest examples for this report.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations were at the forefront of the research. All participants’ data was protected fully throughout and all participants - in whatever form they participated, whether survey, interview or email - provided informed consent.

Particular attention was paid to the potentially distressing nature of discussing the impact of the MIF. The rights of all participants were clarified with them prior to interviews ensuring that they felt comfortable to stop the interview, withdraw consent, withdraw data (until the point of analysis), ask questions, and to skip interview questions. Information was provided on support and offers to suspend or stop the interview were made if interviewees became distressed.

In addition, all GDPR regulations were fully upheld, data from interviews was immediately anonymised with no record kept of the interviewee’s details. The project passed a thorough and detailed examination and consideration of all ethical concerns when submitted to the Humanities and Social Science ethics committee at the University of Warwick.